Pattern History - Se-Jong Tul

King Sejong was a new kind of king. His visionary concerns were rooted in Neo-Confucian principles of benevolence, pursuit of knowledge, and improvement of society. This led to many scientific, technological, artistic and administrative innovations but none as singularly revolutionary as the invention of the Korean alphabet, which would liberate the written word from nobility down to the masses. In August 1418 CE, Sejong became the fourth king of the Chosŏn Kingdom. He was the grandson of the founder of the Chosŏn Kingdom, Yi Sŏngkye. Sejong’s reign lasted 32 years (1418 – 1450). He became the king when he was twenty two years old. Sejong was the third son and not intended to succeed his father. His older brother was appointed as prince but he was notorious. Sejong was a literary person, always reading and studious, opposite from the older brother. He particularly studied the works of Mencius, a Confucian disciple and philosopher who promoted benevolence.

A New Kind of King

The Chosŏn Kingdom was newly established and basic structures were still required. Yi Sŏngkye had chosen Neo-Confucianism as the guiding philosophy of the kingdom and he moved the new capital to Hanyang. Korea was experiencing a time of turmoil and political feuding among the princes. It was an ideal time for a progressive king with the motivation, intelligence and sincere interest to empower the lower uneducated class and create a peaceful and stable society. In his inauguration speech, he said that he would govern the people with genuine benevolence, which is the core of Mencius’ teaching. Confucius believed that benevolence would bring together all classes - politicians, merchants, farmers - to contribute to a harmonious state.

On the second day of his reign, Sejong said something very unusual for a king. He said to his advisers and scholars, “Let’s have a discussion.” He was willing to listen and held regular meetings with lower ranking government officials to get their input. He also established a petition system to hear directly from the people. He felt that a king could always learn more and surrounded himself with scholars and met with them daily and read Confucian texts. The Neo-Confucian vision of the world was one where men lived in harmony with man and nature, not against or apart from them both. Sejong shared the Neo-Confucian belief that if people knew what they should do, they would do it and that ignorance was the biggest societal problem.

With this perspective on his subjects and with his belief in serving them to improve their lives, King Sejong made enormous contributions to establishing legal, education and other basic foundations of the new kingdom. This, he believed, would lay a strong foundation of Chosŏn society — which ultimately lasted over 500 years. His agricultural innovations — including rain gauges and astronomical devices — as well as his promotion of the use of dykes, the water wheel and other irrigation equipment helped increase both farming land and productivity. He revised the tax system to make it reflect the changes in agriculture brought about by those new agricultural techniques. A more accurate agricultural calendar based on improved astronomical instruments was adopted. Legal reforms showed his very modern concern for human rights.

The Invention of Han’gŭl

His most significant contribution, however, was the Korean alphabet, Han’gŭl. Until this time, Korean scholars and bureaucrats relied on the use of the Chinese alphabet. Writing and reading were skills exclusive to nobility and not the common man. Universal literacy was not considered necessary or even desirable. It was seen as reckless to put such a politically important and elite tool as writing into the hands of the people. Sejong wanted people to have direct access to their ruler and that could only happen through writing and reading. An easy writing system would allow information to flow. He also wanted to spread Confucian ethics, and to do so he would have to print books with a simple Korean alphabet to ensure that they would reach ordinary people.

Sejong surprised his government officials when in the winter of 1443, he unveiled his first invention, Han’gŭl. He worked on it like a secret mission because it was first opposed by his top scholars. Before long, women and the lower class used Han’gŭl to write letters and novels and read public announcements that until then been incomprehensible and inaccessible. Sejong remained committed to helping improve access to ideas and knowledge by making improvements in the printing technology. Korea had produced movable type before Sejong but his craftsmen produced an improved font that would be more firmly attached to the printing plate and could thus produce dozens of sheets a day. He then published a number of works from agriculture, medicine and geography, history, and the Confucian classics. These developments and Han’gŭl contributed to a stronger sense of Korean sovereignty and unique Confucian identity distinct from China.

A New Kind of King

The Chosŏn Kingdom was newly established and basic structures were still required. Yi Sŏngkye had chosen Neo-Confucianism as the guiding philosophy of the kingdom and he moved the new capital to Hanyang. Korea was experiencing a time of turmoil and political feuding among the princes. It was an ideal time for a progressive king with the motivation, intelligence and sincere interest to empower the lower uneducated class and create a peaceful and stable society. In his inauguration speech, he said that he would govern the people with genuine benevolence, which is the core of Mencius’ teaching. Confucius believed that benevolence would bring together all classes - politicians, merchants, farmers - to contribute to a harmonious state.

On the second day of his reign, Sejong said something very unusual for a king. He said to his advisers and scholars, “Let’s have a discussion.” He was willing to listen and held regular meetings with lower ranking government officials to get their input. He also established a petition system to hear directly from the people. He felt that a king could always learn more and surrounded himself with scholars and met with them daily and read Confucian texts. The Neo-Confucian vision of the world was one where men lived in harmony with man and nature, not against or apart from them both. Sejong shared the Neo-Confucian belief that if people knew what they should do, they would do it and that ignorance was the biggest societal problem.

With this perspective on his subjects and with his belief in serving them to improve their lives, King Sejong made enormous contributions to establishing legal, education and other basic foundations of the new kingdom. This, he believed, would lay a strong foundation of Chosŏn society — which ultimately lasted over 500 years. His agricultural innovations — including rain gauges and astronomical devices — as well as his promotion of the use of dykes, the water wheel and other irrigation equipment helped increase both farming land and productivity. He revised the tax system to make it reflect the changes in agriculture brought about by those new agricultural techniques. A more accurate agricultural calendar based on improved astronomical instruments was adopted. Legal reforms showed his very modern concern for human rights.

The Invention of Han’gŭl

His most significant contribution, however, was the Korean alphabet, Han’gŭl. Until this time, Korean scholars and bureaucrats relied on the use of the Chinese alphabet. Writing and reading were skills exclusive to nobility and not the common man. Universal literacy was not considered necessary or even desirable. It was seen as reckless to put such a politically important and elite tool as writing into the hands of the people. Sejong wanted people to have direct access to their ruler and that could only happen through writing and reading. An easy writing system would allow information to flow. He also wanted to spread Confucian ethics, and to do so he would have to print books with a simple Korean alphabet to ensure that they would reach ordinary people.

Sejong surprised his government officials when in the winter of 1443, he unveiled his first invention, Han’gŭl. He worked on it like a secret mission because it was first opposed by his top scholars. Before long, women and the lower class used Han’gŭl to write letters and novels and read public announcements that until then been incomprehensible and inaccessible. Sejong remained committed to helping improve access to ideas and knowledge by making improvements in the printing technology. Korea had produced movable type before Sejong but his craftsmen produced an improved font that would be more firmly attached to the printing plate and could thus produce dozens of sheets a day. He then published a number of works from agriculture, medicine and geography, history, and the Confucian classics. These developments and Han’gŭl contributed to a stronger sense of Korean sovereignty and unique Confucian identity distinct from China.

Above: King Se-Jong the Great!

Above: King Se-Jong the Great on the South Korean 10,000 Won note.

Above: The entire 9th Tul Tour Team 2015 with the statue of King Se-Jong the Great, Seoul, South Korea.

Above: Video on King Se-Jong the Great.

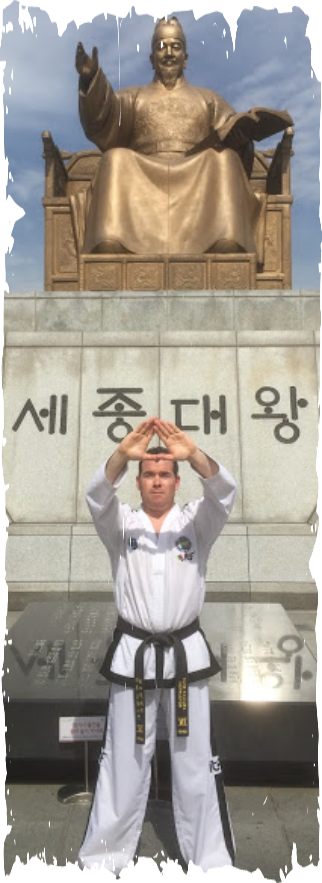

Above: Mr. Kane Raukura, Head Instructor of Dragon's Spirit and 9th Tul Tour Participant 2015. In front of the statue of King Se-Jong the Great. Seoul, South Korea.